Friday, May 19, 2023

Tim Keller, The Prodigal God, and Other Quotes

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

The Fragile, Vulnerable, and Serial Expansion (and Decline) of Global Christianity

Is there some kind of inherent fragility in Christianity that causes it to decline in places where it once prospered, move away from established central locations, and grow in places that are considered to be the cultural margins? The late 20th century missiologist Andrew Walls, in The Cross Cultural Process in Christian History (2002), seemed to think so. I ran across this argument last year right around the time of his death and I have not been able to stop thinking about it. If we consider the supposed weakness and foolishness of the Cross of Christ from an earthly view (1 Corinthians 1), it makes sense.

Walls says,

The history and expansion of the two great missionary faiths, Christianity and Islam, suggests a contrast. While each has spread across vast areas of the world and each claims the allegiance of very diverse peoples, Islam seems ... thus far to have been markedly more successful in retaining that allegiance. With relatively few (although admittedly important) exceptions, the areas and peoples that accepted Islam have remained Islamic ever since. Arabia, for example, seems now so immutably Islamic that it is hard to remember that it once had Jewish tribes and Christian towns, as well as the shrines of gods and goddesses to which the bulk of its population gave homage. Contrast the position with that of Jerusalem, the first major center of Christianity; or of Egypt and Syria, once almost as axiomatically Christian as Arabia is now Islamic; or of the cities once stirred by the preaching of John Knox or John Wesley, now full of unwanted churches doing duty as furniture stores or night clubs. It is as though there is some inherent fragility, some built in vulnerability, in Christianity, considered as a popular profession, that is not to the same extent as Islam. This vulnerability is engraved into the Christian founding documents themselves, with their recurrent theme of the impending rejection of apostate Israel, and their warnings to earthly Christian churches of the possible removal of their candlestick. Neither of these eventualities are seen as jeopardizing the saving activity of God for humanity. I have argued elsewhere that this vulnerability is also linked with the essentially vernacular nature of Christian faith, which rests on a massive act of translation, the Word made flesh, God translated into a specific segment of social reality as Christ is received there. Christian faith must go on being translated, must continuously enter into vernacular culture and interact with it, or it withers and fades. Islamic absolutes are fixed in a particular language, and in the conditions of a particular period of human history. The divine Word is the Qur'an, fixed in heaven forever in Arabic, the language of original revelation. For Christians, however, the divine word is translatable, infinitely translatable. The very words of Christ himself were transmitted in translated form in the earliest documents we have, a fact surely inseparable from the conviction that in Christ, God's own self was translated into human form. Much misunderstanding between Christians and Muslims has arisen from the assumption that the Qur'an is for Muslims what the Bible is for Christians. It would be truer to say that the Qur'an is for Muslims what Christ is for Christians (Walls 2002, 29-30).

In speaking of the expansion of Islam, Walls says that it has been progressive and triumphalist. Mecca was the original center of Islam and it retains that central importance. But, Christianity is different. Walls goes on:

The rhetoric of Christian expansion has often been similarly progressive; images of the triumphant host streaming out from Christendom to Bring the whole world into it come to mind readily enough. But, the actual experience of Christian expansion has been different. As its most comprehensive historian, K.S. Latourette (1945), noted long ago, recession is a feature of Christian history as well as advance. He might have gone on to note that the recessions typically take place in the Christian heartlands, in the areas of greatest Christian strength and influence - its Arabias, as one might say - while the advances typically take place at or beyond its periphery.

This feature means that Christian faith is repeatedly coming into creative interaction with new cultures, with different systems of thought and different patterns of tradition; that (again in contrast to Islam, whose Arabic absolutes provide cultural norms applying throughout the Islamic world) its profoundest expressions are often local and vernacular. It also means that the demographic and geographical center of gravity of Christianity is subject to periodic shifts. Christians have no abiding city, no permanent sacred sits, no earthly Mecca; their new Jerusalem comes down out of heaven at the last day. Meanwhile, Christian history has been one of successive penetration of diverse culture. Islam expansion is progressive; Christian expansion is serial (Walls 2002, 30).

This idea of the serial expansion of Christianity is elaborated further by Walls in an interview in 2000 for The Christian Century. He explains the serial expansion of Christianity through missionary efforts at the margins while decline sets in at what was once the understood center:

If you consider the expansion of Islam or Buddhism, the pattern is one of steady expansion. And in general, the lands that have been Islamic have stayed Islamic, and the lands that have been Buddhist have stayed Buddhist. Christian history is quite different. The original center, Jerusalem, is no longer a center of Christianity -- not the kind of center that Mecca is, for example. And if you consider other places that at different times have been centers of Christianity -- such as North Africa, Egypt, Serbia, Asia Minor, Great Britain -- it’s evident that these are no longer centers of the faith. My own country, Scotland, is full of churches that have been turned into garages or nightclubs.

What happened in each case was decay in the heartland that appeared to be at the center of the faith. At the same time, through the missionary effort, Christianity moved to or beyond the periphery, and established a new center. When the Jerusalem church was scattered to the winds, Hellenistic Christianity arose as a result of the mission to the gentiles. And when Hellenistic society collapsed, the faith was seized by the barbarians of northern and western Europe. By the time Christianity was receding in Europe, the churches of Africa, Asia and Latin America were coming into their own. The movement of Christianity is one of serial, not progressive, expansion.

Walls is asked about what this means theologically, or rather, if this serial decline and expansion has a theological impulse. He believes that it does, and it is wrapped up in the missionary journey of Jesus, the Word made flesh who dwelt among us, and in the inherent fragility and vulnerability of the Cross. As it turns out, the movement of Christianity across the centuries as the body of Christ is formed and reformed amongst the peoples of the earth, looks like and takes the shape of Jesus and His Cross:

Well, this pattern does make one ask why Christianity does not seem to maintain its hold on people the way Islam has. One must conclude, I think, that there is a certain vulnerability, a fragility, at the heart of Christianity. You might say that this is the vulnerability of the cross. Perhaps the chief theological point is that nobody owns the Christian faith. That is, there is no "Christian civilization" or "Christian culture" in the way that there is an "Islamic culture," which you can recognize from Pakistan to Tunisia to Morocco.

The interviewer then asks Walls: "It seems that Christianity is able to localize itself or indigenize itself in a variety of cultures. Do you see this as in some way consistent with the Christian belief in the incarnation?"

Yes. Christians’ central affirmation is that God became human. He didn’t become a generalized humanity -- he became human under particular conditions of time and space. Furthermore, we affirm that Christ is formed in people. Paul says in his Letter to the Galatians that he is in travail "until Christ be formed in you." If all that is the case, then when people come to Christ, Christ is in some sense taking shape in new social forms.

I think cultural diversity was built into the Christian faith with that first great decision by the Council in Jerusalem, recorded in Acts 15, which declared that the new gentile Christians didn’t have to enter Jewish religious culture. They didn’t have to receive circumcision and keep the law. I’m not sure we’ve grasped all the implications of that decision. After all, up to that moment there was only one Christian lifestyle and everybody knew what it was. The Lord himself had led the life of an observant Jew, and he had said that not a jot or tittle of the law should pass away. The apostles continued that tradition. The obvious thing, surely, for the new church to do was to insist that the gentile converts do what gentile converts had always done -- take on the mark of the covenant.

The early church made the extraordinary decision not to continue the tribal model of the faith. Once it decided that there was no requirement of circumcision and no requirement to keep every part of the law, then things were wide open. People no longer knew what a Christian lifestyle looked like. The converts had to work out, under the guidance of the Holy Spilt, a Hellenistic way of being Christian.

Think how much of the material in the Epistles needn’t have been written if the church had made the opposite decision. Paul wouldn’t have needed to discuss with the Corinthians what to do if a pagan friend invites you to dinner and you’re not sure whether the meat had been offered in sacrifice the day before. That was not a problem for any of the apostles or any of the Christians in Jerusalem. They were not going to be eating with pagans in the first place, since observant Jews don’t sit down at the table with pagans. But in Hellenistic Christianity this was an issue. These Christians were faced with the task of changing the Hellenistic lifestyle from the inside.

Walls goes on to conclude that the supposed decline of Christianity in places where it was once strong (Europe and North America) does not mean that Christianity itself is weakening. Rather, as it declines at the center, it grows in what was once considered the margins until those margins become the new center. He says,

There is a significant feature of each of these demographic and cultural shifts of the Christian center of gravity. In each case a threatened eclipse of Christianity was averted by its cross-cultural diffusion. Cross cultural boundaries has been the life blood of historic Christianity. It is also noteworthy that most of the energy for the frontier crossing has come from the periphery rather than from the center. The book of Acts suggests that is was not the apostles who were responsible for the breakthrough of Antioch, whereby Greek-speaking pagans heard of the Jewish messiah as the Lord Jesus, but quite unknown Jewish believers from Cyprus and Greece (Acts 11:19-20) (Walls 2002, 32).

What this means, and what we are seeing now in the world, is that to see the growth of Christianity, we should look to the margins. That Christianity is growing rapidly in the Global South and East should not be a surprise to us. It is the way that Christianity has grown historically. What should hearten us is that through Global Migration where millions of people are on the move from the South to the North and from East to West, the majority of whom are Christians, we see the possibility of renewal of the old Christian centers with the witness and energy of Christian sojourners from the places where missionaries once went bringing the gospel. Those once evangelized now travel back to the sending countries with good news and blessing of their own, if we will have the ears to hear them and faith to receive what God wants to gift us through them.

Kristeen Kim of Fuller Seminary writes in "Migration in World Christianity: Hospitality, Pilgrimage, and Church on the Move" that the church is renewed as it both embraces Jesus as host and migrant, the One giving life and the one receiving ministry through the presence of the vulnerable sojourner. This reality should shape how the church sees itself both as host to stranger and also as the sojourning migrant dependent upon God and both sent into the world and receiving those who come to it with good news. The idea that Christianity is strengthened and renewed as the church engages in racial, holistic hospitality toward the sojourner that is sent to it gives shaped to Walls's view on the serial expansion and decline of the church. More on this later ...

Monday, May 8, 2023

Embracing Limitations in the Vineyards, Redwoods, and Sonoma Coast

Believing that God is the Creator, Sustainer, and Redeemer and that his wisdom far exceeds our own ability to direct, organize, and refashion and recreate our lives according to our own innate desires is key to the Christian faith. It is essential to the confession, “Jesus is Lord.” He is God and we are not and the way he made us, the body and place he puts us in, the talents, abilities, resources (and lack thereof), are all integral to God’s work in our lives. We are only fully alive when we live into the life that God has for us. This isn't some kind of determinism where everything is set for us ahead of time and we have no choice or responsibility other than to morosely accept our state, however wretched it is. Salvation, redemption, hope, and transformation are always in the offering to us. Rather, it's more of a growing into the awareness that God has set us into families and places and nations as our Creator and Designer and has given us bodies and minds and hearts full or real substance. We live in the context of what God has done and is doing in our lives beyond us and in our lived experience. Truly, our lives are not our own and we are not the masters of our universe, able to create and recreate ourselves at will. Our future is not wide open just because we want it to be.

We aren't a blank slate to be remade again and again, but rather, we have been designed by a Creator who is wise and who will glorify himself through us, no matter our condition, if we trust him. Believing that and living into it runs counter to the spirit of the age and requires conversion from self to God. It requires a miracle.

_________________________

In 2019, our family moved from a lifetime in the southeast to pastor a small church in Sonoma County in Northern California, approximately 40 miles north of San Francisco. The move to Wine Country was exciting, but also hard in that our family had to leave behind the life we had lived for years. For me, it required a massive pruning of so much of my work and relationships. Starting over was hard, but I was buoyed by the possibilities of what seemed like an unlimited future, something that had always held appeal to me. What could we do here? What could we accomplish in this place? I was excited and had lots of vision for the church and what was to come. But, I couldn’t see that Covid was looming and about eight months after our family was fully here, we were facing lock downs and massive limitations on even leaving the house.

We endured it the best we could, but so many dreams were dashed. We recovered slowly, but people moved away and things changed. The world became more disconnected. I began to find solace in visitng and exploring the three main features of Sonoma County in the vineyards, the Redwoods, and the Sonoma Coast. What I learned there in the quiet walks by looking down, looking up, and gazing out, became transformative.

But, also, there in the soil of the vineyards, the majestic nature of the trees, the jagged lines of the coast, you see that God has made - He has created - He is Creator - and you, decidedly, are not. The liminal space from land to see is clear. You know when you're passing from one to the next. The trees are distinct. The lines between organisms are fixed. The separation between the expanse of sky and the firmness of terra, of earth and dirt, are clear. Each realm working in its own way, its own function. And all doing their job within the lines that God had drawn for them.

What about me?

It was through stopping, walking slowly, and listening that I have begun to learn to embrace my limitations and let God give me what I need. In exploring this further, I’ve been able to join together with a few others in Sonoma County to form a collective that leads spiritual retreats into the Vineyards, Redwoods, Coast, and Oaks of our region to stop and listen to what God is saying to us through his Creation. We are calling it Signaterra and are hosting personal spiritual and leadership retreats to explore what God is doing in Creation and through our lives so we can go deeper in embracing our God-given limitations and boundaries so that through the concentration of the work of suffering and resurrection, God will produce the best fruit through our lives. Just this weekend, we took a group from our church out on one of these weekends to explore together what God is saying to us through what He has made and it was a blessed time to consider what it means to find our identity in Christ and for God to be Creator and for us to recognize that we are the made, the created.

________________________

Barnabas Osprey, in an essay entitled, "Coming to Terms with our Finite Existence", writes about finitude through the lens of French philosopher Paul Ricoeur. Ricoeur claimed that the "primary task of philosophy is to help us come to terms with our finitude." I’d say its an important aspect of our religion as well. Osprey explains how trying to escape our limitations can lead to all sorts of problems:

Who doesn’t sometimes get angry, sad, or plain frustrated by their limitations? Wouldn’t we all rather have all knowledge, understanding, and power? But our limits are not something to regret, says Ricœur. The real problem is not that we are finite. The problem is that we wish we weren’t finite. In other words, that we want to be God.

This desire to be God is what led to the Fall, as outlined in Genesis 3. Osprey, working through Ricoeur's thinking says,

Genesis 3 teaches that everything went wrong for Adam and Eve when they started to want to be like God. The status of not-being-God is not itself evil or sinful, but it does make evil possible if we refuse to accept our finite status ... We cannot change the fact that we are finite. Things will always happen to us that we didn’t want or choose. We live in a turbulent world in which we are not the master. No matter how intelligent, wealthy, or powerful we are, there are always factors beyond our control that can spoil our best-laid plans. The only choice we have is how we respond to our finitude.

As I grow older, I recognize my finite nature more clearly. Becoming distinctly aware of your mortality doesn't just involve thinking about death. It also involves embracing limitations. I'm in my late 40s now and my children are growing up and leaving home. I have gray hair at my temples and I now wear glasses. The optometrist said that was normal for someone "my age." I've been blind in one eye since birth, so I have always had limitations on my sight and coordination, but now I need help with the one good eye. There are other signs of my finiteness beyond my flagging physical abilities. The future is becoming more narrow. I can see the ruts and grooves of my life more clearly in the emerging lines on my face and my view of the future doesn't seem as wide open as it did when I was 20 years old. My course has been charted and set and I am well along my way in this journey of life as my possibilities narrow. It is hard, but okay to admit that. It can be liberating, actually. I don't have to live or scramble up onto a constant upward trajectory to accomplish or do more. I can be at peace with who I am and trust God for what's next. I can learn, listen, and respond more easily to the nudge of God’s Spirit because I am becoming less inclined to try and make my own way.

This realization doesn't mean that things can't change or that I am powerless to make needed course corrections. Embracing limitations can help us focus and actually be more effective. In a drive to get healthy and embrace limitations regarding my body, I addressed what I was eating and lost 70 pounds last year. I pulled back from engaging social media and just sending my thoughts into the ether in random observations and started a doctoral program to grow and create something more long-lasting. I'm continuing to pastor a church and am focusing more intensely on how people grow deep in grace and a bit less on how to grow a church numerically. And, as my children age and leave home, I’m having to learn new ways of loving them and my wife so we can have a strong and sustainable future as a family spread out and expanding across time and space. All of this requires constant learning, adaptation, and daily repentance from self-focus to others-focus. Change and growth are needed every day. But, part of that change involves learning what it means to be finite, limited, and unable to be all and do all that I'd like. I cannot be anything I want to be, as my young daughter once told me. I do not just "think and therefore I am" as Descartes said. My life is actually informed by time, energy, geography, seasons, relationships, boundaries, and limited resources. Living in to who I really am and who God made me to be apart from expectations and comparisons with others is becoming more key as my life narrows. Context matters and I am more heavily influenced by my environment than I'd like to admit. But, when I do accept that reality of limitation, other possibilities of the spirit open up that were previously kept hidden from me. Spiritual eyes see what physical eyes cannot.

_____________

Admittedly, this perspective flies in the face of the modern zeitgeist. Western Individualism has many good aspects to it. It recognizes that people are unique and have value and certain inalienable rights, and if it is connected to its source in the Hebrew theo-philosophical tradition, it finds that meaning in the Imago Dei; that mankind is made in the Image of God and bears the imprint of the divine upon his soul. But, this worth, value, and dignity isn’t inherent in the human psyche or imagination. We do not have self-creating ability on our own. Our value is derived from our Creator and not just inherent in the self. We are not God and we are not fully autonomous, no matter how far our fingers stretch toward a hoped for self-created future. We have limits and an end. This is unassailable truth no matter how much we deny it. Age teaches us this as time keeps marching on and eventually saps our strength, ideals, and aspirations if they are pointed in fallible directions. Try as one might to change the world, we find it hard to change even ourselves, much less the people closest to us. There are other forces at work and we are not as in control as we hope to be. Rather, we find that things are fairly out of control and our innate fear of loss, and ultimately death, can drive us to cling more tightly to what we know, to our little distractions and escapes, and toward what we think we can create and preserve on our own. And, that fear can often turn us against others in our quest to protect and promote our own established "way of life." Individualism and its attendant anxieties can ultimately isolate and atomize our lives to the point that we fear threats to our autonomy and sense of control over an uncertain future rather than live with a healthy sense of hope. This can lead us to grasp for tribal identities and leaders/saviors to protect us from what might be lost if our fear of losing control is realized.

So what do we do? Osprey, in his further treatment of Ricoeur's philosophy, gives us some options in how we respond to our limitations. Either Refusal or Consent. Osprey continues:

· Refusal means living in angry and bitter resentment against the things we can’t control. It means frustration, shaking our fist at the world and at God.

· Consent means humbling ourselves to say ‘yes’ to whatever situation we find ourselves in, however difficult, however much it is not one we would have chosen. It means embracing our finitude and seeking contentment within the limits that have been given us. And for those who believe in a loving Infinite, consent also means trust. We trust that the origin and goal of all things is good, without any trace of evil. We trust that everything that exists is created by a loving Creator, and that therefore we were created, not for conflict and discord, but for peace and harmony with the creation and the Creator.

Embracing our limitations, our advancing age and mortality, our boundaries, and the fact that we are just a mist on the earth here today and gone tomorrow can actually be liberating. We can dig in deeper where we are, put roots in the ground, and explore what God has given us, the relationships we have, and the wonder of the life we've been given. This is the "consent" that Ricoeur talks about. But, when we are constantly looking outward to extend ourselves beyond where we are and who we are, we can live disjointed lives disconnected from our actual life. We will either try to create a new life altogether through our own efforts (and that will often be applauded by others on the same quest), or we can engage in escapism through seeking to dull the ache of daily living and distract ourselves from the lives we really have. These are all forms of refusal as Ricoeur called it.

But, embracing our limitations as God-given means that we consent and find contentment in our Creator and the life that he's placed us in. Again, this doesn't mean that we settle for mediocrity or that we give up if things are going badly. We can make changes and strive for better things, but we do so as whole people made in God's image with a real substance to who we are, a real identity, a real past, a real context and setting and geography with real relationships and real limitations and boundaries that cause us to go deeper into the ground of trusting God for life, salvation, and sustenance. “Our Father, who art in heaven …. Give us this day our daily bread.”

The Apostle Paul said, in Philippians 4:12-13, "I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want. I can do all this through him who gives me strength." We can be content in any and every situation through Jesus, who gives us strength. We don't have to change our identity or our circumstances to find wholeness and joy. We must be reconciled to our Creator who has the master plan for our lives, and we must be willing to embrace who we actually are in all of our limitations, flaws, weaknesses, and struggles and realize that there is grace for us. God sees us as we are and knows that we are but grass (Psalm 103). He doesn't want us to fix ourselves or the world. He wants us to trust him to do the miracles needed in us. And that requires faith, not in ourselves and what we can do, but faith in God who makes all things new - and who redeems our lives and slowly, but surely, transforms us into the likeness of Christ.

(Note: this is an expanded article from a previous post/draft from January entitled "Embracing Finitude." As it turns out, I have quit a lot to say regarding my finiteness and limitations, and the irony of that is not lost on me.)

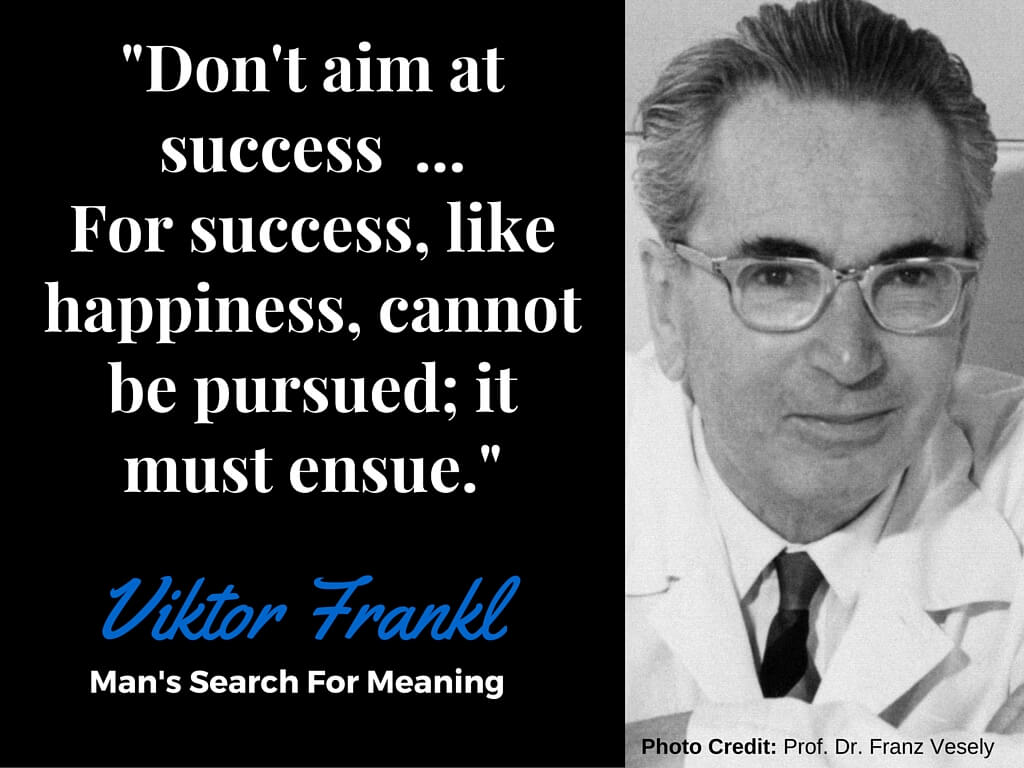

Viktor Frankl on Pursuing Success and Man's Search for Meaning

Viktor Frankl, in his best-selling book, Man's Search for Meaning, says that success is found not through its pursuit for its own sake, ...

-

“Mission societies also sponsored the first international students to gain a higher education in Europe and the United States.” Christian M...

-

Pastor/Theologian Tim Keller passed away today from cancer at 72 years old. He founded Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City and his...

-

(Image: Photo I took of a statue of St. Francis from St. Francis Winery in Sonoma County, California) I've been writing in one form or a...